Many moons ago, I wrote a behind-the scenes of an article I’d published, “The Idea of Terror: Institutional Reproduction in Government Responses to Political Violence.” I wanted to share what it was like publishing a qualitative empirical article on white supremacy and talk through the choices I made in how to present fieldwork material. The piece turned out to be massively popular—more popular, probably, than the article itself—and I’ve heard from folks who used it as a pedagogy tool, grad students who felt seen in what I described, and others who simply enjoyed a glimpse behind the proverbial curtain. So…I’m doing it again.

Last month, the ever-excellent Zoltán Búzás and I published “Racism By Designation: Making Sense of Western States’ (Non)designation of White Supremacists as Terrorists.” Though dealing with similar themes, it’s rather different from “The Idea of Terror” in two ways beyond being coauthored: 1) it’s desk rather than field research, and 2) we submitted it to what I’d consider a more “orthodox” security journal. Both of these factors had implications for how we structured the article and how it was received, culminating in an almost three-year publication journey. (Those of you who have wanted the story: this is the story.)

Since this is a coauthored piece, I’ll be skipping over parts of the article with which I was less involved. Namely, I was the empirics person, which is an unusual role for me. So if you’re interested in insights regarding the norms framework we used and why it’s helpful for seeing racism where racism is invisibilized, you should talk to Zoltán, because that was all him. But if you’re curious about presenting broad swathes of history in persuasive soundbites, explaining technical legal concepts to people used to thinking about them more colloquially, or dealing with a lack of smoking racist guns, I’m your girl. Let’s get started.

Introduction

I care a lot about introductions. I want to be compelled; I want to be dragged into a story. When I can’t find the narrative thread in my own writing, I’ll grasp around for anything I can hold onto, whether it makes sense or not. Which is to say that initially, “Racism By Designation” started with the US’s designation of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), a branch of Iran’s military known for financing and working with Hizballah. I was trying to make the point that terrorist designation is significant by pointing to an example many people had heard of, at least in the US. “This isn’t the best start, Anna,” Zoltán said. “Zoltán I am tired,” I said, sans comma. It wasn’t until the final round of edits on a conditional acceptance that I gave in and went, fine: let’s figure out what the story actually is.

In other words, I can be precious about my own writing, but that usually just results in kicking the can of revisions down the road. If I have a lesson from this that I, too, need to learn, it’s to do it right the first time if you know what “right” is. And “right,” here, meant invoking an example we’d return to later in the article (the Russian Imperial Movement; circular structure always wins) and some extremely damning numbers. I’m usually hesitant to over-rely on numbers to paint a picture, but when they’re this disparate, you just gotta.

A key component of this introduction is describing our empirical strategy as analogous to a court compiling an institutional discrimination case. This way of explaining what we were doing wasn’t in the original draft, but it was part of our response to a rash of comments we got à la “you haven’t proved racism.” The pushback we received darted between “are you sure this is racist” and “maybe it is but there’s not clear causal evidence here,” which are in fact the same argument. To some extent, we brought this upon ourselves by trying to publish a paper based on sense-making and the constitution of white supremacy in a mainstream security studies journal, where positivism rules the roost and racism is mentioned in passing as an “and also” sort of thing, if at all. But it was for a special issue on “race and international security,” born out of the racial justice uprisings and subsequent quasi-reckoning in US political science (“quasi” is doing a lot of work in that sentence), and we had hope. Alas.

Zoltán took care of most of the correspondence with the journal’s editorial team, and he explained that we weren’t operating within a causalist framework; he hoped this paragraph on the empirical strategy would be helpful, and he combed through the article painstakingly to remove any language that could be interpreted as making causal claims. In turn, the editors stated that we hadn’t needed to do this and it would’ve sufficed to find better evidence—but we had been told for three years to “find better evidence” and no evidence we included seemed fully satisfactory. Not wanting to talk about racism and the US security state is not a knowledge problem! At some point, you’re willing to believe it or you’re not. Anyway.

A final note on language: what we call “terrorist designation” in North America is referred to in European academic work as “terrorist proscription” near-exclusively. Anecdotally, this can keep North American and European literatures on the same topic from speaking to each other, which is silly. (Some also use the term “listing”—I blame Gavin Sullivan for this due to his incredible book The Law of the List.) So we wanted to be explicit that we would use these terms interchangeably. Hopefully that makes the article accessible to all English-speaking audiences, regardless of geography.

Disparate Terrorist Designations as Institutional Racism

Welcome to the part of the article I toiled over and that I fully intend to catapult at the “designation happens because of XYZ” crowd. You might consider this the “alternative explanations” section, which tends to get tacked onto the end of positivist political science articles. As we’ve already established, this isn’t really a positivist piece, and I felt it was important to get conventional explanations out of the way first, rather than letting them hang over the piece and inspire doubt until page 30.

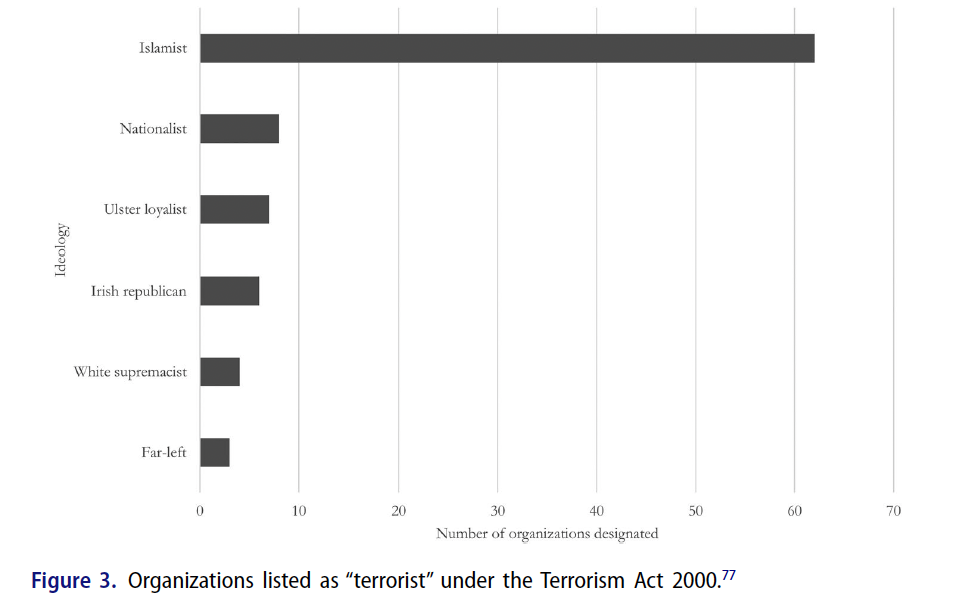

This section was originally much longer, because there are dozens of popular explanations for patterns of (non)designation and I have long, detailed refutations for all of them. We picked and chose due to space constraints and the kinds of pushback we got the most. The table of designations in Australia, Canada, the UK, and the US between 2016 and 2022 was annoying as fuck to make, took up a shit ton of words, and didn’t appear in the first draft: we kept hearing that there were simply fewer white supremacist organizations than other (read: Muslim and/or nationalist) organizations and so the lower designation numbers made sense. The table was my attempt to respond rationally rather than banging my head against a wall to the tune of “not a knowledge problem, not a knowledge problem, not a knowledge problem…” And, as if to drive that point even further home, the table was not enough, and the editors still wanted an estimate of how many white supremacist groups there were globally. I have no idea how to even go about doing this, and to entertain the claim was ultimately to legitimize a way of reasoning committed to sidestepping racism, but I extrapolated an order of magnitude from some other research I was doing on Germany, and this mathematically imprecise method was finally satisfactory. (Because it’s not actually about the math; it’s not a knowledge problem; etc. etc. etc.) So if this section feels belabored: yes. That was how we finally got out of revision hell.

One might term the rest of this section the “anything but racism” section. The majority US folks with whom we interacted in writing and revising this article were generally willing to accept our claims about institutional racism in the UK but much more hesitant about agreeing that racism was structurally present in the US security state. I vividly remember one scholar, a white woman, telling us that she had spoken to some US officials who had told her it was a resource issue (i.e., the State Department didn’t have the resources to track all the white supremacist groups…which, if true, would undercut the claim that there aren’t many white supremacist groups; I digress). She seemed to take this as gospel. I’ve heard similar points from US officials, but they have always been made with a small tilt of the head toward the reasons why there are fewer resources for learning about white supremacy, even if these aren’t fully explicated. This is, of course, the entire point of our article. I digress.

Last thing: it became very clear in our conversations about this piece that people who were not Zoltán and I and weren’t steeped in the designation literature didn’t understand that “designation” was a legal category, even though we told them it was. Here, I’ll dispense with my customary saltiness to make a larger point about the power of colloquial language. Folks are absolutely correct that whom we call “terrorists” informally matters, and they are likewise correct that there can be policy consequences, however indirect, when a political elite invokes this terminology. I don’t blame anyone for thinking this is what we meant—and for this thought to be so deeply entrenched that we had difficulty getting past it. But it goes to show that we (the royal we) do a lot of talking past each other in the terrorism/extremism space, and it is worth it to sit down and really chat about what we mean. So, if our explanations seem repetitive: they are! Words allowing, I don’t think that’s a bad thing.

The next few sections (i.e., Zoltán’s bit)

As mentioned, I’m mostly going to skip over these. I can’t share insights into Zoltán’s writing process or how he reckoned with feedback because I’m not him. He ended up cutting what we might call the “theory” section down quite a bit, largely because reviewers wanted more evidence in the empirical sections (are you sensing a theme), and to make space for that, something else had to go. There’s a lot to unpack there vis-à-vis the relationship between theory and data in political science and to what we give precedence.

What I like about this section is the typology of white supremacist designation’s possible effects that Zoltán proposes. As he puts it, designation can either exemplify defiance (i.e., no designations of white supremacists, in favor of upholding the existing racialization of the “terrorist” category), window-dressing (i.e., reducing contestation by designating a few white supremacists without fundamentally changing underlying beliefs about who and what terrorists are), or transformation (i.e., significantly changing our understanding of the racialization of the “terrorist”). As I argue later, “transformation” isn’t actually possible because of the innate racist purposes of the “terrorist” category. Zoltán is generally more hopeful than I, and I admire this about him. Suggesting this possibility of transformation, only to cast doubt on it later, was our compromise that let both our perspectives remain in the article—and, I think, also probably made it more palatable to an audience less used to thinking about racism. Sometimes you have to be strategic to draw folks in.

Empirical Analysis: Observable Implications and Case Selection

I’ve made this point before, but: the actual reasons scholars have for selecting their cases are rarely the “best” reasons in pure scientific terms. This article is about the US and UK because a) I know a lot about terrorist designation in the US and b) I live in the UK and so was exposed to the most information about the UK. That’s it. I’m sure Canada, Australia, or New Zealand would’ve been equally interesting and informative, but I worked with what was easiest for me. This isn’t scientific, but it’s honest, and it spoke to my actual expertise, rather than diving into cases where others, frankly, know a lot more and where I shouldn’t be writing authoritatively.

Because we submitted the first draft of this article in December 2020 and final copyedits in late June 2023, and because we were writing about contemporary events, the designation landscape changed several times during our revisions. Finally, I made the executive decision that our data would be accurate through February 2022 and after that I’d stop making changes. I think this is reasonable—there are lots of places in the article where we mention specific numbers, and every subsequent need to update increased the risks of missing one of these—and it underscores that data in published work can seem outdated, but that’s the publication process more than any failing on the part of the authors.

There is a lot more caveating in this section than I’d remembered, which I suspect is once again due to our attempts to clarify that we’re not trying to make causal claims, and we still have pretty damning evidence. If I were to start writing this article now rather than in 2020, I’d make fewer claims about a lack of “direct” evidence of racism and more about a lack of willingness to see racism where it is unquestionable. Part of this is a question of audience: do you (the royal you) want to speak to an audience that already believes racism is constitutive of national security institutions and give them some new examples of this and/or some new concepts to think with, or do you want to convince skeptics that racism is in fact present in these spaces? Our article falls somewhere in between, I think, and in that sense falls short of what it could be. I’m grappling constantly with whether it’s worth it to try to make inroads with the skeptical crowd, and I don’t know that I always make the right choice.

Proscription in the United States

(Or, make way for my pixelated Excel graphs; don’t judge me; I made you graphs and you should feel special.)

I’ve started yet another section of an article I wrote with numbers. The apocalypse is upon us. Seriously: I think this strategy works for the audience at Security Studies, and I also try to move on from it relatively quickly to more discursive examples. The latter take more words, which really should open up a conversation about how word counts demand such a high level of knowledge from authors, such that they can pick out the most well-suited examples since they don’t have space to include a full universe of data points. This isn’t a flex, but it is me telling you to take discourse and archival-based research much more seriously. And it returns us to the case selection conversation above: gaining this much knowledge about a brand-new case takes years, which isn’t conducive to the academic publishing model. So why don’t we dispense with contrived explanations for why we choose our cases and privilege deep, contextual knowledge, eh?

The examples I choose in this section come from a pretty wide range of sources. On the one hand, I read a bunch of think tank reports and letters from members of Congress asking for particular groups to be designated; I then spill a fair bit of ink explaining that these asks don’t really matter procedurally. (This was in response to an editor who read an earlier draft as implying that public feedback is part of the official designation process, which it isn’t. Friendly reminder that your writing is never as clear to other people as it is to you!) On the other, I turned to the debate surrounding “terrorism” that’s embedded in the legislative history of immigration regulations in the US, which comes from Congressional hearing records and secondary history literature. There’s a ton more I could say on this front, but I’m saving much of this research for my book—which raises interesting questions I don’t have answers to about prioritization in publishing and the ways that might undermine good science. I’ll just say that the Mary Mourra Ramadan quote I use in this section is absolutely featuring in the book as well, because it’s the sort of detail you can only hope you find. I think I gasped out loud in the Library of Congress’ Law Library reading room, an otherwise unsettlingly silent space. That gasp is how you know you have to include something every chance you get, repetition be damned.

![1995 Senate Judiciary Committee hearing, Mary Mourra Ramadan of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee captured concerns about this power that remain relevant to this day: “Since the President is not compelled to designate every entity meeting the definition [of terrorism], he necessarily must be applying some other unstated criteria to do so.”](http://annameier.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Screenshot-2023-08-08-at-3.48.17-PM.png)

There’s also a small bit in this section on the history of lynching law in the US. This was in response to another request for more evidence. I absolutely think it’s relevant, but I struggle to understand why this area of “security” law was more convincing than the longer treatment of immigration law in this section. Perhaps because lynching reads more obviously as an act of violence to a white audience, whereas much of the violence of immigration is hidden from public view? Perhaps because lynching is more obviously racist? More adventures with the politics of explaining racism. Anyway, that’s why that’s here.

A quick note: I use the term “Islamist” throughout this article to reference a vast range of groups often considered in the same breath as al-Qaeda or the Islamic State. I’ve since learned more about the explicit colonial history of the term “Islamist” and won’t be using it going forward. I encourage everyone to read Asim Qureshi’s careful look at where this term comes from and why, for him, it is irredeemable. After doing more research, I have to agree, and I regret my past use of it.

Normative Challenges: Designating the Russian Imperial Movement

And here’s the circular structure from the intro. I had written about the RIM before for The Washington Post and Lawfare, as well as in my dissertation, so this section felt both very repetitive and very easy. (To reiterate: use your expertise!) The challenge, then, was applying the framework of defiance/window-dressing/transformation to make sense of the designation.

My read of this instance is that it’s window-dressing: one advantage of how long it took to get this published is that we got more and more time to observe that the US government was not, in fact, designating more white supremacist groups. The passage of time also made this initially controversial argument more convincing, I’d wager. Regardless, I don’t recall getting any pushback on this section, which surprised me. My half-baked explanation for this is that the more times you write about a case, the better you get at interpreting it. So, again: lean into your expertise. Fingers crossed this explanation is correct and by the time I write about all the immigration stuff in my book, it’ll be crystal clear.

Proscription in the United Kingdom

As mentioned, the UK is the case I knew comparatively less about at the start of this project. I am deeply indebted to the work of Lee Jarvis and Tim Legrand, which is an incredibly rich and expansive look at proscription in the UK. (Note how my language changed quickly when hopping across the pond!)

In an attempt to replicate the sort of knowledge base I relied on for the US case, I relied on the Hansard (a transcript of Parliamentary debates, analogous to the US Congressional Record and available freely online), lots of news reports, and fantastic secondary literature on the colonial roots of the UK’s terrorism laws. Given the role of immigration in the US’s own legal genealogy, and given the connection between immigration and empire in the UK, I suspected there would be similar stories to tell here, and I was right. Digression, but this speaks to what we mean when we reject the framework of “generalizability” in nonpositivist work but still make claims about knowledge traveling across cases. The UK case is rather different from the US case along many dimensions, which I describe in the article, so the point is not that the exact same factors have the exact same effects cross-nationally. Rather, my knowledge of the US case gave me some indication of where to start in investigating the UK case by suggesting a factor that might matter, even if ultimately in different ways shaped by history and context.

Ultimately, though, this case is shorter than the US case. That’s a reflection of my own knowledge, and I’m sure a UK expert would tell me all of the specific examples I missed, much as I often do the same when people write about proscription in the US for the first time. It’s also because I needed more space to explain the proscription of National Action: the better you know a case, the more concise you can be because you know what matters, and I hadn’t spent years writing about NA like I had about RIM. So, without further ado…

Normative Challenges: Designating National Action

National Action was the first terrorist proscription of a white supremacist group by any country anywhere in the world. Hence, getting it right felt important. The needle to thread here was twofold: first, why 2016? And then: why NA?

Answering the second question was more helpful in determining the degree to which the UK’s proscription constituted window-dressing. But I mention this because I think, if you’re not sure how to start an empirical inquiry, pausing and thinking about what questions are most interesting to answer about a case can be extremely helpful. They can also shine light on where to look for evidence. In the case of NA, asking “why NA” meant looking for calls to designate other, similar groups from around the same time. It also meant asking what, if anything, was different about NA than other groups. Perhaps unsurprisingly by this point, this led to an analysis based on publicity—a factor that also mattered in the US case, albeit in a different way.

And, because the NA case is indeed different, it led to a different sort of evidence—namely, the Hansard transcript of the discussion over NA’s proscription in Parliament. We talk a lot in social science about parallels in case construction and using the same sorts of evidence across cases for maximum comparability. But if we take nonpositivist inquiry seriously, we end up noting that because cases aren’t carbon copies, evidence that might not be the closest thing to a smoking gun in one case is much closer in another. The concise example that drives the point home under the constraints of a word count won’t always be the same across cases, and that’s okay.

Racism, January 6, and the Future of White Supremacist Proscription

(Or, what people less obsessed with fancy section titles would call the “conclusion.” I think the copy editor actually told us informative section titles were a Security Studies editorial policy? One point to Security Studies, who if nothing else assigned us an incredible copy editor. Cheers to Joe, whoever you are.)

We submitted the first version of this article a few weeks before the January 6 insurrection. Initially, I didn’t want to discuss January 6 at all in the article, largely because I was still processing it and also because there wasn’t much space to do so. So we included a line in the article à la “we don’t discuss J6 because it happened too close to publication time.” As “publication time” got pushed further and further into the future, this became a less and less viable excuse.

Ultimately, we decided to use the conclusion to discuss this case. In observing reactions to J6, I had been struck by how intensely politicians and pundits in the immediate aftermath had discussed the possibility of a domestic terrorism statute—a necessary precondition to designating many US-based white supremacist organizations. But this was a play I’d seen before, and as if on cue, the discussion dropped off after a couple of months. The US still has no domestic terrorism statute and no further white supremacist terrorist designees.

As I hope the conclusion makes clear, I don’t think this is a bad thing: focusing on a domestic terrorism statute distracts from the innate racialization of the “terrorist” label and pretends that expanding the label’s use will somehow redeem it. “Transformation,” as we theorize it here, isn’t a real thing within this institutional setting. At the end of the day, I’m glad the long publication process gave us a chance to address J6 head-on, because in a piece full of what I think are damning examples of white supremacy’s role in national security, this is the most damning of all.

We end with nods to two pieces that have been formative in my own understanding of racism in the US, and to which I’ll offer an extra nod here because you should read them too. The first is Joe Soss and Vesla Weaver’s “Police Are Our Government,” in which they develop the concept of “race-class subjugated communities” in what I find to be a particularly convincing construction of the interdependent roles of race and class. We don’t talk about class in the article, not really, but it’s there and is an important step for future research, I think, to square the circle of how governments treat leftists across racial lines. The second piece is Victor Ray and Louise Seamster’s “Against Teleology in the Study of Race.” Ray and Seamster are sociologists, and Ray’s work on racialized organizations in particular has helped me articulate the foundational role of racism in US society. So let me make a final point here, building on my earlier discussion of the range of sources we use in this article: cross-disciplinary citation is how I make sense of white supremacy and (counter)terrorism. We make these discussions of what gets called “terrorist” violence only about the “terrorism” literature at our own intellectual peril.